This is a summary of the published article Pesticides in the Great Barrier Reef catchment area: Plausible risks to fish populations

We were motivated to provide evidence on what the community & landholders value. Creating impactful science might mean scientists need to go outside the standard scientific approach and look for ways to reach the broader community on the things that matter to them.

- Key Findings

- Recommendations

- Pesticide levels in waters flowing to the Great Barrier Reef are high enough to affect fish health, their food and habitat and leave them susceptible to other stressors.

- These pesticides are found in areas that are crucial nursery habitats for important fish species, such as Barramundi and Mangrove Jack.

- No scientific studies have specifically investigated if pesticides are causing declines in fish populations in these waterways, even though the mechanisms and conditions are present to indicate they could be.

- Inspire environmental stewardship with evidence on the organisms and ecosystems that people value and use the most, rather than just what is scientifically standard.

- Invest in research and monitoring to understand if pesticide contamination is affecting important fish, like Barramundi and Mangrove Jack.

- Better understand the health of the Great Barrier Reef’s freshwater ecosystems to support the Reef’s health and resilience and are highly valued by its residents.

Before the investigation, we knew that the Great Barrier Reef ecosystem is threatened by pollutants like nutrients, sediments, and pesticides, that come from land-based human activities and transported by rainwater that runs off the land into creeks, wetlands, rivers and then out to the coast and into the marine environment.1 Improving the water quality that drains into the marine environment involves the cooperation of many people and groups to change how their activities on the land can reduce the amount of pollutants that end up in creeks and rivers.

Most of the scientific evidence focuses on demonstrating the impact of poor water quality on organisms that are most likely to encounter mortality.

The catchments are a critical socio-ecological system, with residents deeply valuing freshwater habitats, fish populations, and recreational activities in these areas, and also playing important roles as environmental stewards for improving water quality.2

However, the scientific evidence for improving water quality in these areas is often for the purpose of protecting the Reef with little attention focusing on whether water quality is affecting the species and habitats that hold high value to residents living in the GBR catchments.

Therefore, rather than just focusing on protecting the reef’s coral and seagrass habitats, emphasizing how declining water quality impacts culturally/recreationally important freshwater fish species could inspire better environmental stewardship among catchment area residents to benefit the entire reef system.3

This study was conducted to investigate whether pesticides from agricultural runoff are potentially harming recreational and culturally important fish populations in the rivers and coastal areas around the Great Barrier Reef.

What we discovered

There is widespread contamination of herbicides and insecticides from agricultural runoff in the waterways draining into the iconic Great Barrier Reef system during the wet season.

The main evidence supporting this:

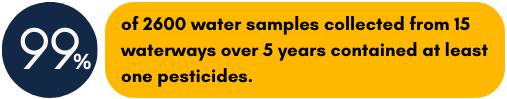

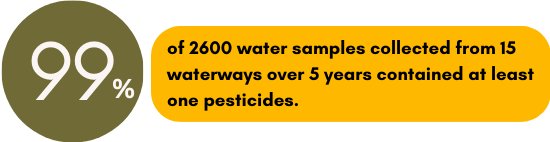

- Almost all (99.8%) of 2600 water samples collected from 15 sites between 2010-2015 contained at least one pesticide.

- The most commonly detected pesticides were herbicides like 2,4-D, atrazine, diuron, hexazinone, and the insecticide imidacloprid.

- Atrazine and 2,4-D were detected in around 68% and 52% (respectively) from over 3700 samples collected between 2011-2016.

- Imidacloprid was detected in 54% of more than 6500 samples collected from 14 catchments, over xx years. In some catchments it was detected in up to 99.7% of samples.

- The ubiquitous presence of pesticides in fresh, estuarine and marine waters of the GBR region means there is high potential for aquatic organisms to be exposed to these pesticides.

There is widespread contamination of herbicides and insecticides from agricultural runoff in the waterways draining into the iconic Great Barrier Reef system during the wet season.

There is spatial and temporal overlap between periods of high pesticide runoff into critical aquatic habitats that many important fish and crustacean species rely on during their life cycles in the Great Barrier Reef catchment area.

The main evidence supporting this:

- The areas where high concentrations of pesticides occur (i.e. lower coastal floodplains of waterways) provide important habitat for many ecologically, recreationally, and culturally significant fish and crustacean species in the Great Barrier Reef catchment area.

- More than 80 fish species utilize the floodplain wetlands of the GBR, with at least 70 species having a diadromous life cycle requiring migration between freshwater and marine habitats like estuaries and coral reefs at different life stages.

- Important recreational and commercial fish species like mangrove jack, barramundi, eels and mullet move between the interconnected habitats of floodplains, wetlands, estuaries and offshore reefs during their life cycles.

- Freshwater crustaceans and mussels residing in floodplains and wetlands are also susceptible to PAI exposure.

- These aquatic habitats and their connectivity are under pressure from urban/agricultural development, leading to a net loss of over 7600 hectares of natural wetlands in the GBRCA between 2001-2017, although the rate has slowed recently.

- With fish likely inhabiting areas with elevated PAI concentrations and facing other environmental stressors, there is a need to examine the physiological mechanisms by which PAI toxicity could occur and impact these valued species.

Although the levels of pesticides detected in GBR waterways may not directly kill fish, there are demonstrated sublethal effects and indirect ecological pathways through which these pesticides could still negatively impact valued fish populations in the Great Barrier Reef catchment area.

The main evidence supporting this:

- The pesticide concentrations regularly exceed ecological toxicity thresholds and are likely to adversely affect some aquatic species populations, though not at levels expected to outright kill fish.

- Fish inhabit these waterways during critical life stages when they are most likely to be exposed to PAIs.

- Pesticides more commonly detected can affect fish at a metabolic level, such as impacting hormone levels and causing endocrine disruption.

- Sublethal effects from pesticides exposure could stress fish and reduce their resilience against other environmental stressors.

- Pesticides can indirectly impact fish by harming the organisms and habitats that fish depend on for food, shelter, oxygen, and nutrient cycling.

- Mechanistic and “systems biology” studies have identified plausible pathways through which sublethal pesticide exposures could detrimentally impact fish health and physiology, even if not acutely lethal.

| Pesticide type | Chemical name | How often is it detected | Potential impacts to plants and algae (food & habitat) | Potential health impacts to fish | Potential lethal impacts to fish | Potential health impacts to insets & crustaceans (food) | Potential lethal impacts to crustaceans (food) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herbicide | Atrazine | Commonly | ❌ | ❌ | 🟢 | ❌ | 🟢 |

| Herbicide | Diuron | Commonly | ❌ | 🟢 | 🟢 | ❌ | 🟢 |

| Herbicide | Metsulfuron-methyl | Occasionally | ❌ | 🟢 | 🟢 | 🟢 | 🟢 |

| Fungicide | Chlorothalonil | Occasionally | 🟢 | 🟢 | 🟢 | ❌ | ❌ |

| Insecticide | Imidacloprid | Commonly | 🟢 | ❌ | 🟢 | ❌ | ❌ |

| Insecticide | Fipronil | Rarely | 🟢 | ❌ | 🟢 | ❌ | ❌ |

| Insecticide | Chlorpyrifos | Rarely | 🟢 | ❌ | 🟢 | ❌ | ❌ |

🟢Indicates that concentrations of this pesticide were detected below concentrations that have been recorded in published scientific studies to cause impacts to the health (i.e. not death) or survival of fish or crustaceans.

We say these are potential impacts as these effects on fish and crustaceans were not observed, rather we use the concentrations of the pesticides that have been detected as an indicator of whether the impacts could occur. The presence of a pesticide detected in an ecosystem does not indicate its potential to cause adverse effects.

Pesticide are only considered to pose a hazard to organisms if they occur at concentrations greater than those that cause toxic effects.

Investigation methods

| WHAT evidence was collected | HOW evidence was collected | WHEN evidence was collected |

|---|---|---|

| Presence of pesticides in fish habitats | Water quality monitoring data from 15 rivers and creeks analysed for pesticide concentrations* + Evidence published in scientific literature | 2010 – 2015 |

| Pesticide impacts to fish | Literature review: 27 publications | 2003-2022 |

| Pesticide impacts to fish habitat and food | Literature Review: 28 publications | 1992-2022 |

| Impacts to fish from other stressors (nutrients, turbidity, hypoxia) | Literature Review: 16 publications | 2002 – 2022 |

Science in Action

A behind the scenes look at the making of this research…

About these results

Scientific quality statement

Limitations of the study

Acknowledgements & funding

References

- Australian Government and Queensland Governments, 2018; Waterhouse, Schaffelke, et al., 2017; Gordon, 2007 ↩︎

- Gordon, 2007; Walker & Salt, 2006 ↩︎

- Marshall et al., 2019 ↩︎

Leave a comment